I watched Hunger, a 2023 Thai movie that is currently streaming on Netflix, the other night; I am a sucker when it comes to movies set in the culinary world. That stems back to the pleasantly surprised enjoyment I had watching Jon Favreau’s Chef when it landed on streaming platforms years ago and continues with Bradley Cooper’s Burnt and a healthy dose of television series No Reservations with the late Anthony Bourdain.

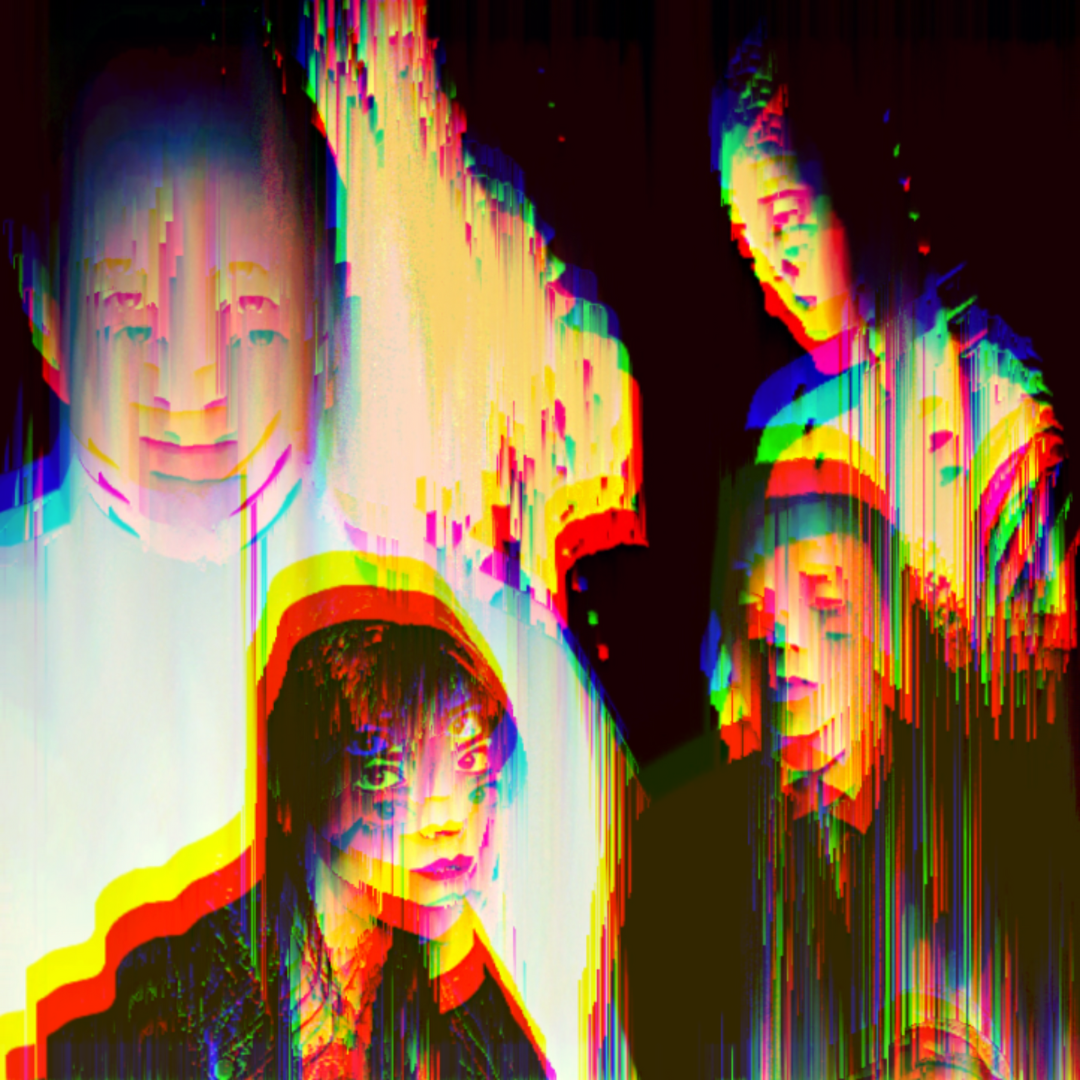

Throughout Hunger, we are haunted by the malevolent Chef Paul; a character that demands perfection with his cooking, but at times for principled reasons. Our protagonist, a street cook named Aoy whisked out of the slums of Bangkok to the cordon bleu world of high cuisine. We soon discover the horror of Chef Paul, but instead of a scorned chef akin to Ralph Fiennes’ character in The Menu, the horror comes from a place of societal elitism – Chef Paul refuses to cook for people who cannot afford his food.

For Chef Paul, his narrative regarding growing up in a poor family and providing the drive to become a world-renowned chef has led to no resentment of the upper class. It’s a resentment towards those with a lower economic status, demonstrating a character riddled with poverty shame and can ill afford now to show a semblance of sympathy towards that socio-economic class. Be it to preserve the allure of his cuisine, which we see become primitive savages when eating his food, or perhaps self-defence from the shame felt growing up impoverished.

There are parallels between both Hunger and The Menu with regard to how the higher class are treated within the constructs of the narrative. They are viewed as vapid, ignorant (at times stupid), oafish and above all else, riddled with hubris compared to their lower-class counterparts. The Menu played with the idea of a chef fed up with what he once loved becoming the proverbial millstone by those that elevated his career but with their own ulterior motives, while Hunger played with the concept of a chef who would happily guild adulation from a class of patrons he quite clearly has a resentment for.

Chef Paul is misanthropic, yet is an incredibly good chef who believes his status as “the” elite chef for the socialites he still resents means he is above the law (gentle spoiler there). Chef Slowik is a broken genius who has lost his love for cuisine from the socialites that take the concept of eating for granted. Slowik is a much more sympathetic character, given we see through the movie someone who lost their lust for something because it became unappreciated and loveless through its shallow popularity – those people don’t care about the food, the care to be seen at an establishment rather than want to try the cuisine.

Kind of how Coachella or Glastonbury became less about the music and more about the culture and “scene” at the music festival. Almost akin to New York Fashion Week, albeit the point of those runway shows is about being seen as much as it is about the catwalk collections.

But Chef Paul has few sympathetic elements to his character; his few redeeming moments in the film exist in the end purely for the self-preservation of his “brand.” This is an interesting flip during Hunger where we start to feel his motives are, while incredibly hostile, with good intentions. But there is a reason for this also; should his branding suffer from a mistake by his team of chefs, he is no longer as powerful of a societal figure as he once was. This pragmatism becomes more about his survival than the concern of his patrons. Remember – they have been portrayed as vapid entities that shift immediately from one “hot” trend to another.

The finale of Hunger is none more evident of the clientele. But Chef Paul has few sympathetic elements to his character; his few redeeming moments in the film exist in the end purely for the self-preservation of his “brand.” This is an interesting flip during Hunger where we start to feel his motives are, while incredibly hostile, with good intentions. But there is a reason for this also; should his branding suffer from a mistake by his team of chefs, he is no longer as powerful of a societal figure as he once was. This pragmatism becomes more about his survival than the concern of his patrons. Remember – they have been portrayed as vapid entities that shift immediately from one “hot” trend to another.

This throws up a few questions; is Hunger as much of a heightened horror as The Menu? Quite clearly there is a visceral element of horror in The Menu with its gore and deaths that take place throughout the evening of fine dining. But there is also a horror element in Hunger, a more existential take on the horrors of humanity – while not visceral as The Menu, the scares come from how shallow the upper class are, how easily malleable they can be through someone higher up the social hierarchy and how downtrodden those not in the same economic class are made through “some” elitist figures (hashtag “not all rich people”)

Horror, especially heightened horror, has shown that you don’t need to splash the screen with buckets of viscera, nor be utterly transgressive with the violence shown on screen (though sometimes, in the case of Ti West’s X, it helps drive the cinematic era the director strives for i.e grindhouse film, euro horror). Hunger’s horror comes more from a very real place of the callous nature we see sometimes from those from wealth; be it a misguided attempt to show their support despite not reading the room (nor their recent box office payslip) through to a pure, sometimes admirable in its honesty disdain towards, to quote I’m Rich You’re Poor, “povvos.”

If we treat the idea of heightened horror as something that doesn’t need to rely on gory horror tropes, then yes – Hunger can be considered a form of a heightened horror movie, with its horror more existential than physical. Having said that, it also taps into some unnerving set pieces at times that do give a visual presentation of physical horror to give an optic of the bizarre. Kind of how Brian Yuzna did with Society, only a little less shunting; the Winona Ryder and Christian Slater black comedy Heathers could also lend part of itself to this existential horror theory.

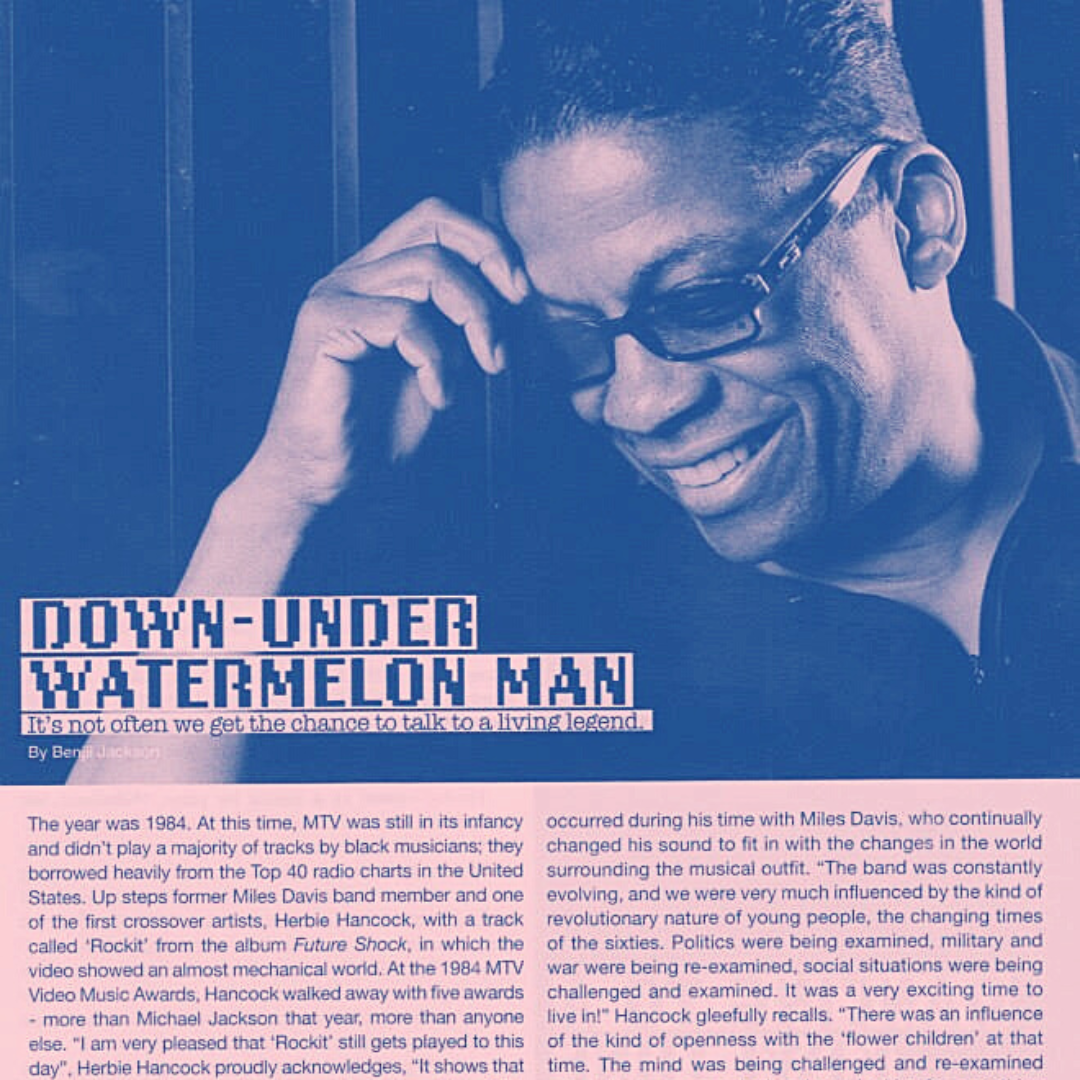

The second question both movies have brought up also is; are we about to enter a period of “foodie horror” or “cordon rouge” subgenres? The key elements between both The Menu and Hunger are the elitist, almost enlightened influencers and “foodies” Both The Menu and Hunger explore the concept of elitism in culinary world and how it can lead to consequences.

In these movies, the “foodies” and influencers are depicted as being so consumed by their desire for the perfect meal that they are willing to overlook or even participate in immoral actions, but more white crime than cold blooded – a safer form of criminal activity, very tennis court in the prison yard energy.

This portrayal of the elite as morally bankrupt and disconnected from reality is a common theme in horror movies, particularly in slasher films where victims are often portrayed as superficial and deserving of their fate. However, in foodie horror, the focus is on the perpetrators of horros rather than the victims, as the audience is forced to confront their own complicity in supporting a system that values the pursuit of higher social status over basic human empathy.

In contrast to slasher movie victims, who are often objectified and punished for their perceived sins, the foodie horror genre highlights the danger of unchecked privilege and the need to question our own values and priorities. As such, both films offer a unique entry into both the culinary movie and, hopefully if I’ve convinced you, the heightened horror genre.